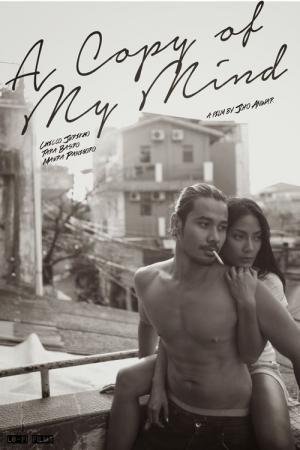

Joko Anwar’s A Copy Of My Mind – A Jakarta Story, an Indonesian Story

by Faiza Mardzoeki

Jakartans will be very familiar indeed with electricity cables criss-crossing, tangled, chaotically marring their glimpse of an ever dirtily greying sky. So too the repeating call to prayer echoing along Jakarta’s narrow lanes and alleys coming from the city’s hundreds of mosques. Then there is the jagged sounding symphony of traffic noise as every kind of vehicle zig-zags also chaotically on streets and tollways vomiting their suffocating exhaust fumes.

Joko Anwar’s realistic depiction of the living environment of Jakarta city’s working and lower, lower middle class is part of an overall approach which is marked by a strong empathy for the people whose story he relates. The main characters are Sari (Tara Basro), a salon worker doing facials every day all day, and Alek (Chico Jericho), who survives earning his pittance by using google on his laptop to translate the dialogue for pirated DVDs. They are portrayed with great empathy without sacrificing any realism. Joko Anwar is able to portray a very credible romantic relationship, touching and realist in its picture of what brings two people together in the ocean of coincidence that is life among the teeming population of Jakarta. It is touching and realist too in the depiction of the indekos room eroticism of such a romance.

This empathy with the two main characters is echoed in how almost all other characters are treated: the Chinese couple savouring their nightly dance in the busy food court, the Auntie absorbed in her nightly TV infusion, the urban poor complaining about their pay to attend an election rally, the imprisoned rich corruptor ridiculing herself, Sari’s fellow salon workers – all are portrayed with a gentle realism originating from a palpable empathy. Even a physically cruel torturer is portrayed as part of an environment relentlessly merciless against its poorer inhabitants all of whom are aware that there is something better: a garden their kids can play in.

At the same time there is no empathy with the elite creeps who are shown as the ultimate source of the catastrophe that is the life of the poor. The rich corruptor is somehow able to be portrayed with empathy in prison, but is exposed as a vicious self-interested creep as are her fellow corruptors, when portrayed at her work outside gaol. Sari’s pseudo-upper-class boss is initially an entertaining character providing some amusement to the audience but is later revealed as having another less amusing side.

This empathy is also reflected in the film’s politics. The story of Sari and Alek and their momentary intersection with the elite is set against a presidential election campaign. The campaign is like a background activity which has no impact on their lives as events unfold and will clearly bring no change. The noise of the “pesta demokrasi” is irrelevant in the same way as the thousand calls of prayer from the mosques each morning is irrelevant to the real spirituality of the characters, who don’t pray but are no less loving, and heroic.

A Copy Of My Mind answers our longing for films that can capture the reality of contemporary Indonesia, in particular Jakarta, as it is experienced by the vast majority. This is the experience of the millions that come to Jakarta from towns and villages around the country hoping for a better fate. But they can’t escape the poverty. They can’t get out of the crammed and sweaty living quarters. This is the life of Sari and Alek. That is all they can hope for. There is no hope of a garden for the kids to play in as is dreamed of even by the cruel torturers doing the filthy bidding of their bossed in the elite above them.

Themes such as these are too often neglected by today’s film makers as if Indonesia has no real stories to tell. Too many films are bogged in the fantasy world of realising dreams told with no anchoring in reality, far from the day-to-day life of the majority. Or they take that other route to escape preaching a morality that it is claimed will guarantee entry later ion into heaven.

Joko Anwar presents his film with simplicity, occasionally embellished with happy amusement, but also not avoiding the bitterness of reality. Where there should be suspense, there is and it is well-done. This film takes Anwar’s work to a new level beyond that represented in his earlier films (Janji Joni, Kala, Pintu Terlarang). This simplicity, its empathy and realism is made possible not only by Anwar’s script and direction but by the high craft of the actors and clearly their own empathy with the characters, large or small.

There is one contradiction of this film that needs comment as it exposes one of the tragic challenges of Indonesian film. As a film combining a love story and aspects of a crime thriller convincingly and vividly set among Indonesia’s real people, it could be extremely popular if it were able to reach that mass audience, with a revolutionising impact on dominant film tastes. But one wonders whether its English language title, A Copy Of My Mind, mysterious even to the native English speaker, will be too mysterious and alienating for the mass audience. At the same time, it is possible that not enough of the audience that might relate to the title will come to see the film. A mysterious title might be irrelevant if such a film had a big budget for promotion in the cinemas and particularly on television, where some of the alienating mystery can be diminished with preview clips and advertising. It will be a loss to Indonesia if A Copy Of My Mind does not reach the people whose story it tells.

A Copy Of My Mind takes us on a very intimate journey. This is transmitted through dialogue and visuals that themselves are intimately in touch with the harsh, hard and cramped reality, and with its moments of optimism, about which the story tells. The intimacy captures Sari and Alek’s moments when they can put aside the harshness of their surrounds and the exhaustion it produces.

A Copy of My Mind invites us to think again on the reality of Jakarta and Indonesia. The day-to-day reality of the majority. This is the real intimacy. (2015)